Creator:

Isidore Isou

Performer:

Isidore Isou

Witness:

MarcʼO

Gil J. Wolman

François Dufrêne

Jean-Louis Brau

Maurice Lemaître

Guy Debord

Bibliographical sources:

DEVAUX Frédérique, Chapitre 4. La carrière du traité en 1951-1952, pp.55-67.

DEVAUX Frédérique, Chapitre 7. L'année 1952, p.127-135.

in DEVAUX Frédérique, Le cinéma lettriste (1951-1991), Paris, Editions Paris Expérimental, 1992, 320p.

DEBORD Guy, DEBORD Alice, RANÇON Jean-Louis, pp. 42-43.

in DEBORD Guy, DEBORD Alice, KAUFMANN Vincent, RANÇON Jean-Louis, Guy Debord, Œuvres, Paris, Editions Gallimard, 2006, 1904 p.

DEVAUX Frédérique, Chapitre 7. L'année 1952, p.127-135.

in DEVAUX Frédérique, Le cinéma lettriste (1951-1991), Paris, Editions Paris Expérimental, 1992, 320p.

DEBORD Guy, DEBORD Alice, RANÇON Jean-Louis, pp. 42-43.

in DEBORD Guy, DEBORD Alice, KAUFMANN Vincent, RANÇON Jean-Louis, Guy Debord, Œuvres, Paris, Editions Gallimard, 2006, 1904 p.

Producer:

Isidore Isou

Occurence:

Places:

Starting date:

04 20 1951

Topology:

Background:

on the fringe of the IVth Cannes International Film Festival

Producer:

Marc'O

Adress:

Cannes

Objets:

Exemple de ciselures sur une pellicule de Isidore Isou

Technique description référence:

Exemple de ciselures sur une pellicule de Isidore Isou

Image extraite de <em>Traité de bave et d'éternité</em>

Technique description référence:

Image extraite de <em>Traité de bave et d'éternité</em>

Documents:

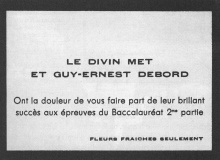

Faire-part de réussite au baccalauréat de Henri Met (dit le Divin Met) et de Guy Debord (qui ne forme qu'une seule et même personne)

Type:

Imprimé

Technique description référence:

Faire-part de réussite au baccalauréat de Henri Met (dit le Divin Met) et de Guy Debord (qui ne forme qu'une seule et même personne)

Affiche du film réalisée par Jean Cocteau

Type:

Imprimé

Technique description référence:

Affiche du film réalisée par Jean Cocteau

Portrait de Guy Debord devant une de ses inscriptions à la chaux.

Type:

Imprimé

Technique description référence:

Portrait de Guy Debord devant une de ses inscriptions à la chaux.

Sortie de la projection de <em>Traité de bave et d'éternité</em>

Type:

Imprimé

Technique description référence:

Sortie de la projection de <em>Traité de bave et d'éternité</em>

Guy Debord, Jacques Fillon et Marc'O en visite chez Jean Cocteau

Type:

Imprimé

Technique description référence:

Guy Debord, Jacques Fillon et Marc'O en visite chez Jean Cocteau

Nice Matin, dimanche 20 avril 1951, p. 1.

Type:

Presse

Technique description référence:

Nice Matin, dimanche 20 avril 1951, p. 1.

Nice Matin, dimanche 21 avril 1951, p. 10.

Type:

Presse

Technique description référence:

Nice Matin, dimanche 21 avril 1951, p. 10.

Nice Matin, dimanche 27 avril 1952, pp. 4-8.

Type:

Presse

Technique description référence:

Nice Matin, dimanche 27 avril 1952, pp. 4-8.

Le Festival était hier en récréation

Type:

Presse

Technique description référence:

Le Patriote Cannes, 11 avril 1951, p. 3.

Fichier pdf:

Il n'y a pas que les projections...<br />Le film Traité de bave et d'éternité d'une longueur de 5200 m, tourné par Jean Izidore Isou, sera présenté la semaine prochaine hors programme.

Résumé retranscription:

Il n'y a pas que les projections...

Le film Traité de bave et d'éternité d'une longueur de 5200 m, tourné par Jean Izidore Isou, sera présenté la semaine prochaine hors programme.

Le film Traité de bave et d'éternité d'une longueur de 5200 m, tourné par Jean Izidore Isou, sera présenté la semaine prochaine hors programme.

Aujourd'hui dernière journée du Festival

Type:

Presse

Technique description référence:

Le Patriote Cannes, 20 avril 1951, p. 3.

Fichier pdf:

La journée d'aujourd'hui<br />Clôture du Festival.<br />Au programme en plus des projections dans la grande salle du Palais, dont on trouvera plus loin l'énoncé, ce matin à 9h30 dans la salle du cinéma Vox, rue d'Antibes, projection du film Traité de bave et d'éternité.

Résumé retranscription:

La journée d'aujourd'hui

Clôture du Festival.

Au programme en plus des projections dans la grande salle du Palais, dont on trouvera plus loin l'énoncé, ce matin à 9h30 dans la salle du cinéma Vox, rue d'Antibes, projection du film Traité de bave et d'éternité.

Clôture du Festival.

Au programme en plus des projections dans la grande salle du Palais, dont on trouvera plus loin l'énoncé, ce matin à 9h30 dans la salle du cinéma Vox, rue d'Antibes, projection du film Traité de bave et d'éternité.

Le Patriote Côte d'Azur, Juin 1993.

Type:

Presse

Technique description référence:

Le Patriote Côte d'Azur, Juin 1993.

Fichier pdf:

Isidore Isou, qui fréquentait la toute nouvelle Cinémathèque Française, adorait le cinéma et avait envie de faire un film. Il emprunta une caméra et réalisa son grand rêve qui était, au niveau des vues cinématographiques, de rendre celles-ci caduques en tant que reproduction du réel, c'est à dire de faire de celles-ci des supports à des manifestations diverses, et donc montrer que ce qui est important, comme dans la poésie, ce ne sont plus les ensembles - le poème, le mot- mais l'émiettement des particules.<br />De la même façon qu'on avait fait un sort à la lettre en poésie, au cinéma, on ne s'intéressait plus à l'ensemble, le plan, par exemple, mais à sa destructuration, à son émiettement. De façon plus générale, il faut se reporter à la théorie d'Isidore Isou, à savoir que pour lui, tout art passe par deux périodes : une première dites "amplique" de construction, donc d'amplification, et la seconde dite "ciselante", de repliement et de parcellisation, de recherche des pratiques fondamentales d'un art : la lettre dans le cas de la poésie, dans le cas du cinéma et de la photo, le grattage du support, donc des particules physico-chimiques.<br />Propos de Frédérique Devaux recueillis par Eric Paul dans <em>Le Patriote - Côte d'Azur</em>, Nice, Juin 1993

Résumé retranscription:

Isidore Isou, qui fréquentait la toute nouvelle Cinémathèque Française, adorait le cinéma et avait envie de faire un film. Il emprunta une caméra et réalisa son grand rêve qui était, au niveau des vues cinématographiques, de rendre celles-ci caduques en tant que reproduction du réel, c'est à dire de faire de celles-ci des supports à des manifestations diverses, et donc montrer que ce qui est important, comme dans la poésie, ce ne sont plus les ensembles - le poème, le mot- mais l'émiettement des particules.

De la même façon qu'on avait fait un sort à la lettre en poésie, au cinéma, on ne s'intéressait plus à l'ensemble, le plan, par exemple, mais à sa destructuration, à son émiettement. De façon plus générale, il faut se reporter à la théorie d'Isidore Isou, à savoir que pour lui, tout art passe par deux périodes : une première dites "amplique" de construction, donc d'amplification, et la seconde dite "ciselante", de repliement et de parcellisation, de recherche des pratiques fondamentales d'un art : la lettre dans le cas de la poésie, dans le cas du cinéma et de la photo, le grattage du support, donc des particules physico-chimiques.

Propos de Frédérique Devaux recueillis par Eric Paul dans Le Patriote - Côte d'Azur, Nice, Juin 1993

De la même façon qu'on avait fait un sort à la lettre en poésie, au cinéma, on ne s'intéressait plus à l'ensemble, le plan, par exemple, mais à sa destructuration, à son émiettement. De façon plus générale, il faut se reporter à la théorie d'Isidore Isou, à savoir que pour lui, tout art passe par deux périodes : une première dites "amplique" de construction, donc d'amplification, et la seconde dite "ciselante", de repliement et de parcellisation, de recherche des pratiques fondamentales d'un art : la lettre dans le cas de la poésie, dans le cas du cinéma et de la photo, le grattage du support, donc des particules physico-chimiques.

Propos de Frédérique Devaux recueillis par Eric Paul dans Le Patriote - Côte d'Azur, Nice, Juin 1993

''

''